Abstract

Transnational Professor Bishnu Pathak is the creator of the Peace-Conflict Lifecycle, the architect of Human Security Studies, the founder of the Principles of Process Documentation (End-to-End-Lifecycle) of any development project and the pioneer of Process Documentation for Interfaith Peacebuilding Cycle. Arduous Mr. Pathak is a professor of human security studies who holds a PhD in inter-disciplinary “Conflict Management and Human Rights”. Immense versatile personality Prof. Pathak is born into a poor family in a remote mountain. His parents were without the aid of alphabet, absolute illiterate.

Prof. Pathak has been working as a Commissioner at the Commission for Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons for the sake of truth, justice and reparation for dignity. He is the Board Member at TRANSCEND Peace University, Petitioner to the UN for Total Disarmament, Vice President at the Global Harmony Association, and Founding Chairman at Peace and Conflict Studies Center.

He is the author of more than 100 international papers and has coauthored several books on human security, DDR-SSR, civil military relations, conflict transformation, peace, human rights, community policing, federalism, principles of harmony including Nepal’s 2008 Constituent Assembly Elections: Converting Bullets to Ballots, East-West Center Bulletin. His book Politics of People’s War and Human Rights in Nepal (2005) is a widely circulated volume. Many of his phenomenal publications are incorporated as references in different Universities across the globe.

Busy and dedicated schedules always keeps him in low innocent profile. He presents himself genuinely among the populace pursuing “do no harm” approach and follows either win-win or lose-lose game theory, especially reflected in his (conflict) transformative works. A generalist Prof. Pathak’s major ideas are measured through freedoms doctrine. He is committed to continue his exceptional contributions in future through unwavering teachings, researching, and writings for the universal social betterment. On top of that, his innovative analyses are mostly drawn from yesterday’s publications, experiencing intricacies today, and hopes for basic needs and freedoms met universe tomorrow. His entire works advocate for a world without war to ensure safety of children, men and women in schools, homes and jobs. His prime thrust is to liberate the people from injustice, inequity, indignity, insecurity, intolerance, inharmony, and inhibition which are found widespread in the society. Trans-disciplinary Prof. Pathak firmly believes that injustice happened anywhere is a struggle to justice everywhere.

Introduction

The creator of Peace-Conflict Lifecycle, the pioneer of 12-different definition of Human Rights, the architect of Human Security Studies and the founder of the Principles of Process Documentation (End-to-End-Lifecycle) of any development project and Process Documentation of Interfaith Peacebuilding works, Prof. Pathak is a versatile personality in today’s world. Prof. Pathak who has published more than 100 research papers internationally, always keeps him in low profile and present genuinely among the populace pursuing “do no harm” approach. In any dialogue or negotiation he was involved in, he prioritizes the win-win or lose-lose game theory.

The objective of the study is to let people know what Prof. Pathak has phenomenally contributed to exhume the truth, justice and dignity for the sake of global peace and harmony, and honest development of successful Interfaith Peacebuilding cycle. The paper particularly follows both primary and secondary information with theoretical, practical and participant observation assessments. The information was primarily gathered through networking tracking methods and indirect-direct and informal-formal interview processes. Its analyses are mostly drawn from yesterday’s learning through past publications, experiencing difficulties today, and hopes for basic needs and freedoms met universe tomorrow. It begins with a synopsis of the author’s profile.

Let us brief who Prof. Pathak is. He was born in Fulbari-5, Taplejung district in 1963 into a poor family. Taplejung is a very remote district in the hill and mountainous region that links with Tibet, China. In a family with nine children, he was the eighth child. His parents were absolute illiterate due to both the severe poverty of the family and inaccessibility of school. They would thus affix their thumb impressions instead of signing the names. Having been born to such a family, he joined school in 1973 at grade 3, but hardly attended the classes as he had to support his parents to look after the buffaloes, cows and goats. He grew-up there chasing away the monkeys from dawn to dusk to save the maize grown in his tiny patch of land. He had to walk two hours uphill every morning through the scary jungle full of tigers and other wild animals and take the same way back home in the evening. He would eat whatever meals available at home in the morning and in the evening. He had a firm principle to go against the discrimination, exclusion, marginalization, distrust and indignity. At the age of 14, he was once detained for three nights at the police custody at the district headquarters while he protested teachers’ autocracy, for instance, severe teachers’ punishment such as beating, hair pulling, teasing to girl-students, and so forth. He was also expelled from school one year later as he advocated for multi-party democracy in 1978. While he migrated to flat-land (Tarai/Madhes) in 1979, he continued his further studies being a private tutor for junior levels students. He holds an interdisciplinary doctorate in Conflict Management and Human Rights from Tribhuvan University (1998-2004). He worked as a Visiting Researcher at the Danish Center for Human Rights (1999-2000) as a part of PhD research. Some of the major ideas of Mr. Pathak are measured through freedoms doctrine.

Freedom of Association

He mostly holds volunteer positions for conflict transformation, peace, harmony, human rights including transitional justice and human security in a number of institutions all over the world. Among others, the following list gives a glimpse of Prof. Pathak’s involvement and arduous contribution.

- Commissioner, Commission for Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons, Nepal[1]

- Board Member at the TRANSCEND Peace University (TPU)[2] and Professor of Human Security Studies[3] and Civil Military Relations[4], Germany.

- Founding Chairman and Director at the Peace and Conflict Studies Center (PCSC)[5], Nepal.

- Vice President, Global Harmony Association[6], Moscow, Russia.

- Editorial Board Member, World Journal of Social Science Research[7], Los Angeles, USA

- Chief Coordinator, Petition to the UN for Global Disarmament Now[8]

- Peace, Security and Human Rights Expert, Wikistrat, USA and Australia[9]

- Editorial Board Member, Academy of Scientific and Applied Research Journals, UK[10]

- Executive Member, WorldWide Peace Organization, Argentina[11]

- Advisory Board Member, Journal of Internal Displacement, Canada[12]

- Convener, South Asia, TRANSCEND International, Germany[13]

- Panellist, Japan Association for Human Security Studies, Tokyo, Japan[14]

- Member, Insight on Conflict, Peace Direct, United Kingdom[15]

- Council Member, International Peace Bureau, Switzerland[16]

- Research Committee Member-Security and International Relations, Center for Global Nonkilling, Honolulu, Hawai, USA[17]

- Board of Advisors, Existential Harmony Project and World Conference, IASE Deemed University, Gandhi Vidya Mandir, India[18]

Prof. Pathak belongs to a poor, small and landlocked country Nepal, which is sandwiched between two giant neighbors – China and India. Nevertheless, he works for a global community advocating the principles of harmony to enable every one of us to live in a just world.

Freedom to Contribution

Professor Pathak has been working as a Commissioner at the Commission for Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons (CIEDP). It is to be noted that people of the countryside were victimized during a decade old armed conflict (1996-2006); the same people were exploited during peace process (2006-2012); but again they were or are ill-treated in the name of transitional justice (2013-) in Nepal. To conclude the transitional injustice, the CIEDP has already initiated its tasks to examine, document and evaluate the complete truth of the cause and nature of disappeared persons inviting applications from victims and others; investigate ante-mortem data and whereabouts of the disappeared persons and victims, provide post-investigation information to the victims’ families and others; assist in restoring or reintegrating the victims’ dignity in the society testifying disappeared person’s belongings, evidences, and testimonies; and recommend reparations to the victims’ families and prosecution against the perpetrators[19].

While Prof. Pathak had been working as a Founder President and Director at the PCSC, he led the team to design, implement, monitor and evaluate the human rights training to the ex-combatants of the Maoist Army in Nepal (2008-2009). He was also involved in providing training to the former combatants on Disarmament Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR), Security Sector Reform (SSR), and global experiences relevant to conflict transformation and democratization process. Besides, he has also been involved in up-skilling the senior security officials in conflict management, military (re)integration, civil-military relations and democratization process. These activities were found to be most influential in reconciling the peace process in Nepal. He had also worked as a Country Director on Police Stations Visitors’ Week (2009-2012) under the Altus Global Alliance, New York where he developed and published Approaches to Citizen-Centric Policing[20] (2011), first of its kind.

He has authored more than 100 research papers from abroad and articles related to conflict resolution, peace, security, DDR-SSR, civil military relations, community policing, UN, human rights, and federalism including “Nepal’s 2008 Constituent Assembly Elections: Converting Bullets to Ballots” published in the East-West Center Bulletin (2008)[21]. His pioneer work on “Peace-Conflict Lifecycle” has been included in the book Experiments with Peace published from Norway in 2010. Among many other publications, his book Politics of People’s War and Human Rights in Nepal (2005)[22] is a widely circulate volume which has been incorporated as a reference book across the continent. Nepal finds more vulnerable to violent conflicts owing to discrimination, exclusion and more inclusion.

Focusing to Conflict Transformation Theory for Peaceful World, Prof. Pathak outlines the contribution of Professor Johan Galtung, Father of Peace Studies, in freedoms dimension: freedom of association and mediation; freedom from want and fear, experiment, structural violence and contradiction; and freedom to inherit peace and construct peace theory, which may be new of its kind[23]. Galtung’s theory of peaceful conflict transformation is one of the most significant achievements of traditional peacemaking.

Freedom in Participation

Prof. Pathak had worked as a Senior National Peace, Security and Human Rights Expert on Joint Evaluation of the International Support to the Peace Process in Nepal (2006-2012) from 2012-2013. The main purpose of the evaluation was to contribute to the continued enhancement of the support to the peace process and transitional justice from the focal development partners and others. In addition, the evaluation was anticipated to contribute to the persistent learning in relation to supporting peace processes, peacebuilding and transitional justice efforts in conflict-affected and post-conflict situations elsewhere. The evaluation was focused on the contributions made by Denmark, Switzerland and Finland from 2006 to 2012. The evaluation adopted an implicit theory of change based approach pointing out conflict drivers: poverty, power relations, inequality and violence. The changes were brought about by the full implementation of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA). Pursuing traditional OECD/DAC program evaluation criteria, the evaluation sampled programs and processes to determine relevant, effective, efficient, and sustainable impact indicators. Besides, the evaluation assessed how development partners have contributed to the peace process following the coordinating mechanism.

Prof. Pathak had worked as a Senior National Conflict and Peace Expert at the European Union Program in the Conflict Mitigation Package, Conflict Prevention and Crisis Management Unit in Nepal from 2002 to 2003. He was assigned to assist in mitigating the human rights violations and abuses against the civilians in the remote areas; support development workers as potential “middle mediators” in the grass-root diplomacy and recovery programs; enhance the local communities capacity to negotiate with the armed Maoist insurgents and security forces; coordinate NGOs, CBOs and project’s users groups in the implementation of projects’ activities; engage in conducting a survey of existing conflict prevention approaches and practices; and discuss with the European Commission project team leaders on the findings of the survey in dimensions of peace, conflict and human rights[24].

A project run by the Welt Hunger Hilfe (WHH) under the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) recruited Prof. Pathak as a Senior National Security and Risk Assessment Expert. The roles and responsibilities of the consultant were to evaluate the security/safety information and risk management framework for the project activities and areas; plan and implement crisis management in the project areas integrating safe and effective development process; and develop and train the project staff to work in post-conflict situation, understanding “Do No Harm” principle in development process and establish staff security and project working environment at the community/project areas as a whole[25].

The United Mission to Nepal (UMN) conducted a Process Documentation Research on Interfaith Peacebuilding work from community to national levels hiring Prof. Pathak as a Senior Interfaith Peacebuilding Expert in the post-conflict Nepal. The principal objectives of this task were to document how interfaith networks and other beneficiary groups were formed, what strategies and approaches worked and what worked less well, and what were the key turning points. Similarly, it was also mandated to capture information about changes of perceptions and relationships among different stakeholders; document to which extent brought positive changes in knowledge, attitude and behavior of intended beneficiaries and how challenges were mitigated and opportunities were utilised; analyze impact on conflict prevention and resolution in terms of gender sensitivity degree; and identify bottlenecks, inefficiencies, and lessons learnt[26].

Being one of the dearest pupils (2000-2007) of Professor Johan Galtung, Prof. Pathak was invited to work as a Convener of the TRANSCEND International[27], South Asia (2003-) as a Board Member of the TRANSCEND Peace University[28] (2008-) and as a Professor of Human Security Studies from 2013. He is involved in governing the University by establishing networks on broad policies, programs, and objectives and searching, reviewing, selecting and developing the courses. He has been initiating and developing the papers on concept, origin, development and theory of human rights. He pursues the differences between human security and human rights. As a professor, he evaluates each student’s overall performances, and quality of paper produced by each student under his supervision. Recommending him as an immense versatility and capabilities, Professor Galtung writes, “he is very trans-disciplinary, a generalist concerned with social betterment without becoming superficial… very transnational…capable of seeking problematic situations from the angles of nations inside and outside Nepal”[29].

Being a Vice-President of the Global Harmony Association[30], he developed a course on Interfaith Harmony and Harmony in General[31]. Prof. Pathak had also published a paper entitled Principles of Religious and Interfaith Harmony[32]. He has also developed Principles of Harmony[33], a new of its kind. Harmony and peace go hand in hand. Peace is the process for perfection whereas harmony is a perfect relationship. Peace may be experienced alone by a person whereas harmony is a systematic character between two or more persons or parties; harmony is always a plural condition. Peace implies calmness; harmony requires unity[34]. Prof. Pathak has defined Nepal’s peace process as a harmonious relation at the beginning, which has later turned out to be competitive among the political parties and finally harmonious relation has been transformed into inharmony[35].

Prof. Pathak was recruited as a Field Coordinator by the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Conflict Research, Harvard University in 2001 which he produced a substantial report on conflict prevention. It objectively developed a roster of participants to participate in the conflict preventive initiatives in Nepal; contacted the selected participants explaining the aims and strategies of Web Conference; provided the name and password to each participant to log on and put their comments on the conference; facilitated to exchange vision, mission and goal among the scholars around the world on conflict prevention strategies; disseminated the information among the Nepalese participants and prepared the brief report and submit to the concerned institution[36].

Prof. Pathak worked as a Guest Researcher at the Danish Centre for Human Rights (DCHR)[37], Copenhagen during the years 1999 and 2000. The DCHR has been his first University to learn about fundamental human rights and international humanitarian law. That occasion provided him with a unique opportunity to share how armed conflict called People’s War left impacts on right to life, liberty, justice and dignity. It has learnt that till there is injustice and insecurity, the respect, protect, promote and fulfillment of all human rights for all shall never be achieved. In this sense, it can be argued that fruits of human rights and humanitarian law shall vegetate in a civilized world with the concept of lenience for peace and non-acceptance to conflict, tension and war.

He was involved as a Researcher at the Center for Peace and Conflict Studies (CPACS), at the University of Sydney (June 2010 to March 2012). He carried out a process of critical discourse on political conflict analysis particularizing for the Peace Journal (PJ) headings in the sense of influencing audience responses and perceptions; noted about a dozen particular articles and news items exercising critical discourse analysis under PJ; and produced a report, listing all the stories about conflict that appeared in the media and ‘scored’ according to the content analysis model[38].

The Police Station Visitors Week (PSVW) was a unique global event organized by Altus, the Global Alliance to assess the quality of services the police departments delivered, identified some of the best practices used by the police, and strengthened the accountability of police to the local citizens whom they serve. Nepal also initiated annual visits by groups of citizens to local police stations, coordinated globally and designed to produce comparable annual scores on five dimensions of police services. Such measures were community orientation, physical condition, equal treatment of the public, transparency and accountability, and detention conditions where Prof. Pathak worked as a Country Director from 2009 to 2012. Thus, it contributed to improving trust between police and communities that led to greater reliance on police by crime victims and also improved access to justice[39].

Freedom on Human Security

Prof. Pathak developed a course on Human Security Studies, which was perhaps the first one of its kind in the world. He has written a number of papers on Human Security. A few of them are: Origin and Development of Human Security (2013)[40], Human Security and Human Rights: Harmonious and Inharmonious Relations (2013)[41], Female Combatants, Peace Process and Exclusion (2015)[42], Civil-Military Relations: Theories to Practices (2012)[43], Civil-Military Relations in Nepal (2010)[44], Women and DDR in the World (2011)[45], Approaches to Citizen-centric Policing (2011)[46], Disarmament Demobilization and Reintegration And Security Sector Reform in Nepal: A Preliminary Sociological Observation (2010)[47], Child Soldiers: Crime against Humanity (2009)[48] and Tarai-Madhes: Searching for Identity-based Security (2009)[49] and among others.

He states that human security is complementary to human rights. According to him in 2013, it is a comprehensive, interrelated, and coordinated concept that encompasses freedom from want, freedom from fear, freedom to live in dignity, freedom to take action on one’s own behalf, and freedom to inherit pro-nature environment for forthcoming generations as fundamental rights. All individuals such as poor, disadvantaged, vulnerable and marginalized have equal and unrestricted opportunity to enjoy their rights and freedoms. In this regard, the United Nations also has the foremost objective to unite, strengthen, and maintain peace and human security where human security focuses on the betterment of human lives by conquering over poverty, hunger, disease, illiteracy, armed conflict, and terrorism through mutual respect. Human security itself respects human rights and human rights are there to safeguard human security. All governments, either from the developed or the developing countries, realize the importance of human security for all the people by ensuring their survival, livelihood, liberty, and dignity. Human security strives toward protection of the nation and/or state formulating national security policy by putting the people at the center. He writes that human security minimizes military spending and increases humanitarian security and action, irrespective of class[50], birth, geography, sex, caste/ethnicity, religion, profession, culture, and others. Moreover, Prof. Pathak articulates human security as pro-people, pro-jobs, pro-resources, pro-nature and pro-universe[51].

Human security and human rights are the universal phenomena. Prof. Pathak argues that human security and human rights are harmonious to inharmonious natures. Human security is nation-state to people-centered notion, whereas human rights are human-centered approach. Human security underscores as inherent, inalienable, interdependent, multidimensional, and non-derogatory rights and freedoms whereas human rights are the core of them. Human rights are guided by international treaties, legal instruments, and humanitarian laws whereas human security yet exists such definite parameters. According to him, human security is a neologism, but an integrated concept, however human rights has a long history. Security protects human’s basic needs, resources, and capabilities, whereas rights act to respect or preserve them. Security assists to reduce differences of rights implementation while State suppresses some rights in the name of maintaining the law and order. Human security tries to ensure safety to all including asylum seekers, whereas rights demand to implement legal measures[52].

Prof. Pathak says that there is a contesting (many cases) and reciprocate (some cases) relationship between human security and human rights to advocate its spirit: survival, liberty, life, and dignity of person. Human security has three generations: Civil-Political Rights, Socio-Economic and Cultural Rights, and Collective Rights similar to human rights. He further classifies human security into five additional generations: Right to Truth for Justice, Right to Peace for Harmony, Right to Dignity for Security, Right to Sovereignty for Independence, and Right to Shared Responsibility for Unity[53].

Freedom for Human Rights

Prof. Pathak defines human rights as moral, legal and cultural relativism privileges and advocates that human rights are to liberate the person from injustice, inequality, indignity, insecurity, intolerance, inharmony, and inhibition which are found widespread in the society. The defining principles of human rights are given below:

- Philosophy: Philosophical rights are based on the concepts of human dignity, self-reliant, paramount and the egalitarian rights.

- Nature: Natural rights are universal, inherent, non-derogatory, inalienable and self-evident.

- Political: Political rights are the respect for the integrity of life, the right to liberty of movement, freedom and participation in political life.

- Civil: Civil rights are enforceable rights to citizens, physical integrity and safety, protection from discrimination and insecurity, right to adult franchise, and equal participation in economic, social and cultural life.

- Legal: Legal rights are a rule of law, equality before and under the law, and protection from all kinds of injustices.

- Social: Social rights are to ensure an adequate standard of living, the right of family, fraternity, solidarity, non-discrimination and self-determination.

- Economic: Economic rights are to work and distribute resources for the adequacy of basic needs such as food, housing, clothing, and healthcare.

- Culture: Cultural rights are participation in cultural life, customary practices, the right to minorities and the right to education.

- Religion: Religious rights are for a secular nation, freedom to change his/her belief and intolerance based on faith or religion.

- Class: Class rights are to reduce disparities between rich and poor; end of unequal wage, prejudice, and exploitation; and initiate equitable resource distribution, social friendship, social harmony, cultural promotion, political participation and inclusive nation state.

- Worker: Worker rights are a right to unionize, firmly implementation of national laws and international employment standards, and equitable distribution of benefits of productions between employees and employers.

- Owner: Owner rights are rights not to unionize at workplace; liable for loss and profit; ensure safe working place and environment; and right to hire, suspend, promote, dismiss, and distribute bonus to workers respecting customary practices, national laws and international instruments[54].

Human rights are a child of laws that continuously and steadily enrich through the needs, demands, resources[55], capabilities and knowledge of human beings. Knowledge has the freedom to think, turn-out (generate) and turn-on (act).

Freedom at (Interfaith) Peacebuilding

It is to be noted that evaluation looks upon success and failure of any project, but never takes attention of its process. The Der Evangelischer Entwicklungsdienst (EED) developed a network for Local Capacity for Peace (LCP) in South Asia. United Mission to Nepal (UMN) is one of the LCP members in South Asia. While EED international evaluators found a unique successful model in UMN’s Interfaith Peacebuilding[56] Network, it decided to carry out an extensive research on its Process Documentation (PD). The PD is a socio-cultural science approach which is generally carried out at the end of the (piloted) project to determine the Theory of Change. The UMN formally recruited Prof. Pathak to analyze the change of perceptions: to mitigate the challenges, to utilize the opportunities and to identify the lessons learnt.

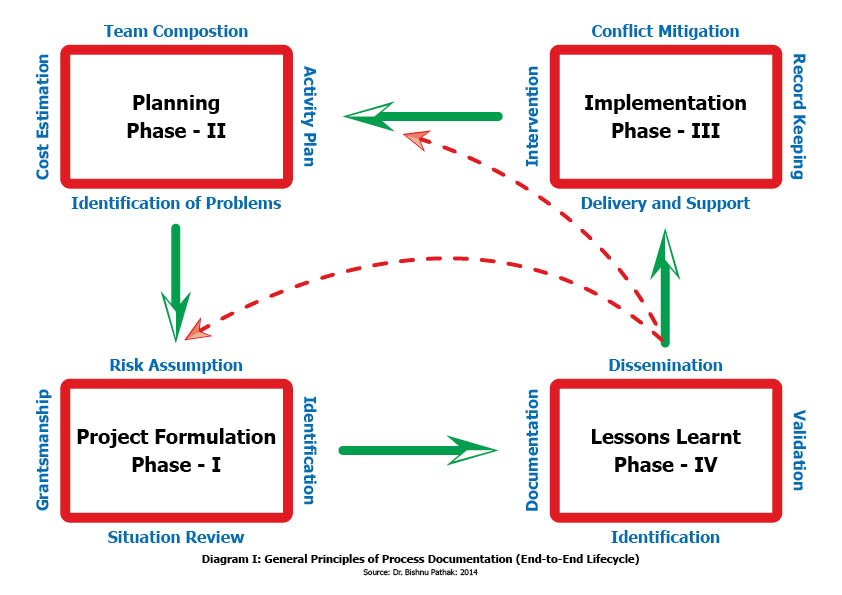

Prof. Pathak finds out that Process Documentation is a ‘lessons learnt-centric’ piloting method that mostly applies at the community level in developing or post-conflict countries to resolve the troubled issues. The process has a definite lifecycle and moves in an anti-clockwise direction and completes at the end of it on project implementation process. This is called an End-to-End Lifecycle which has its own lifecycle rather like an ecosystem[57], which may be first of its kind in the world. Its cycle completes with lessons learnt (post-implementation/ phase IV), implementation (phase III), planning (pre-implementation/ phase II) and project development (phase I) (See Diagram I).

Each individual phase follows initiation, preparation, continuation and completion of the activity. The sole purpose of the Process Documentation is to maximize the positive impact and minimize the negative impact on the programs.

The interfaith peace programs in Nepal are undertaken as problem-solving or conflict transforming, strategic interventions of peacebuilding at the community level. The Interfaith Peace Projects are conducted by UMN Cluster offices located in Sunsari and Rupandehi districts in Nepal.

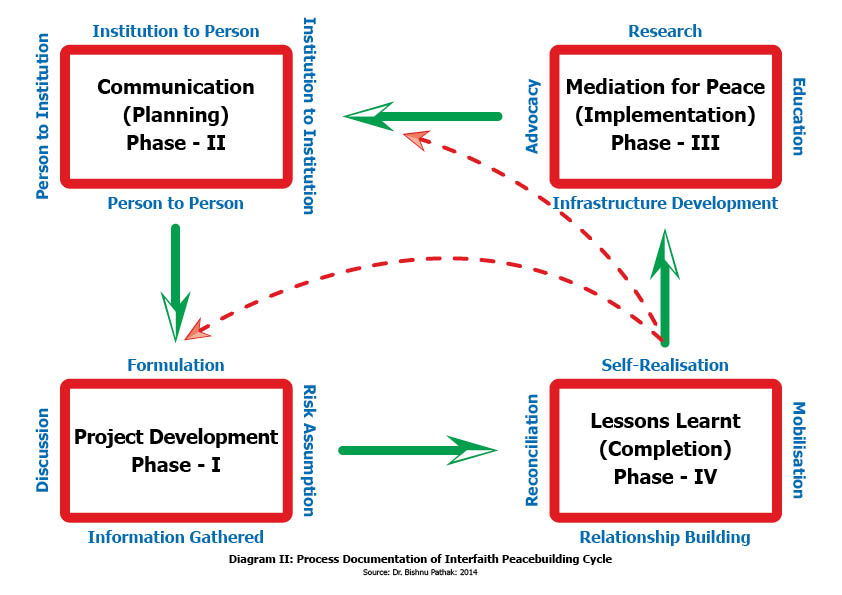

Prof. Pathak’s patterns of Process Documentation on Interfaith Peacebuilding Initiatives follow right-to-left (anti-clockwise) direction which means the process documentation of the project begins after the completion of the (piloted) project as illustrated in Phase IV of the project cycle diagram and documents in the opposite direction to the normal project cycle. Relationship building, self-realization, reconciliation-forgiveness and mobilization are the principal findings from project’s final report, final evaluation and final reviews (see Diagram II). The diagram II is no less than a Theory of Change for the interfaith peacebuilding programs.

Prof. Pathak concludes that the PD of interfaith peace applies to resolve conflicting issues empowering grassroots-level community people, encouraging indigenous techniques and utilizing the local resources in developing countries like Nepal and beyond. It eliminates mistakes, cutting down time, reducing costs and improving the quality and efficiency of a particular task, activity or project. The PD is a short-term technique as a feasibility study to implement the long-term projects that fulfill all the peacebuilding requirements. The study found Theories of Change on situation analysis, relationship building, community mediation, reconciliation, self-realization and acceptance.

The process should follow the clockwise direction for future bigger programs unlike anti-clockwise process to support and care for emergency and relief programs. According to Prof. Pathak, an integrated interfaith peacebuilding program in the community-level is no less than “to the people, for the people and by the people”.

Freedom from Armament

Prof. Pathak is the Chief Coordinator for the Petition to the UN for Global Disarmament Now. The main objective of the petition is to reduce the enormous military spending, dissuade the development of nuclear weapons and increase humanitarian intervention for basic livelihood: food, shelter, health, and education. There are 11 coordinators working for the Petition ranging from East to West and South to North, namely India, USA, Nigeria, Ghana, Australia, Ukraine, Russia and Bangladesh. All coordinators are from reputed Universities with a sound academic background on conflict transformation, peace and harmony. He stated that human beings are alarmed at the huge resources that go into military spending and the development of nuclear weapons, while a large section of the world’s people go without their basic needs met. The world shall never be secure from armed violence or war if children, men and women have no security in schools, in their homes, and in their jobs. Thus, the UN for Total Disarmament is for ourselves, our children and grandchildren.

Disarmament eventually leads toward a world without wars. Prof. Pathak truly accepts what UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon had said in 2012, “Disarmament and nonproliferation be inculcated at every school and in every student around the world”[58]. Total disarmament will ultimately help strengthen human security, fulfill basic needs of the people and promote genuine peace, harmony, human rights, justice, and development[59]. Besides, Prof. Pathak has been involved in various negotiation and mediation processes between the conflicting parties and has worked as a resource person for the democratization process of the security forces and former Maoist combatants in Nepal.

Freedom from Hegemony

Based on the geo-political reality, Prof. Pathak published a paper on Impacts of India’s Transit Warfare against Nepal[60] (2015) in a journal – World Journal of Social Science Research. The paper is well appreciated within and beyond the author’s homeland. Besides this, he has written a number of papers including India’s Seven Freedom Doctrine to Nepal (2014)[61], Insecurity in Security[62] (2011), Struggle for True Sovereignty[63] (2010), Nepal India Relations: Open Secret Diplomacy[64] (2009), Federalism: Lessons from India[65] (2009), The Koshi Deluge: A History of Disaster for Nepal[66] (2008), Role of India and Madhes Movement in Nepal[67] (2008), Silvering Lining of Nepal’s Monarch and Role of India[68] (2008) among others.

Nepal promulgated the New Constitution with signatures of 90 percent of the Constituent Assembly (CA) II members on September 20, 2015. The world congratulated Nepal for its success, however, as Prof. Pathak noted, Nepal’s roji-roti-beti[69] (closest) neighbor India sent a cold-note and a mild-warning. India informally conveyed a proposed 7-point constitutional amendment the following day supporting 10 percent of Nepal’s CA II, which included the agitating Tarai-Madhesi groups. Prof. Pathak further noted that such amendment suggestions interfered the landlocked Nepal’s sovereignty and internal affairs. Moreover, India initiated an undeclared transit trade warfare, blockading Nepo-India borders. Because of sudden unjust blockading, Nepal has been suffering from an acute shortage of cooking and oxygen gas, gasoline, medicines and other daily humanitarian supplies. Worse still, India’s transit warfare was enforced in a period when Nepo-China borders were blocked by the devastating Earthquake. India’s proposed Amendment in the Constitution for Madhesi groups is merely a farce; clearly the myopic interest of India is to control Nepal’s natural resources and to restore the Hindu Kingdom in the name of insecurity in Nepal[70].

Ranjit Rae, India’s Ambassador to Nepal, gathered the agitating Tarai-Madhes leaders in the Embassy just before the Prime Minister’s election and said, “The winning of Oli as the Prime Minister of Nepal is a defeat of India”. Rae further hurt the Nepali as he followed Goebbels’ style of reporting to New Delhi. As a result, angry masses display arson effigies of India and PM Modi across the country ranging from Tarai, Hill to Mountain[71].

Commenting on Impacts of India’s Transit Warfare against Nepal, veteran intellectual Professor Mohan Lohani stated that Prof. Pathak’s excellent scholarly paper throws light on how a transit country like India seeks to strangulate a landlocked country Nepal. He further argues, “It is a well argued paper that should be read by all our policy makers”[72]. Dr. Satish Chandra Gupta writes, “…yourself being seemingly staunch Gandhian”[73]. Land rights scholar Buddhi Narayan Shrestha says, “Border blockade from India has been internationalized by your paper.” Diplomat Dr. Rita Thapa says, “Despite the India blockade, Nepali spirit continues to survive… With the help of scholarly Nepali like yourself, Nepal will thrive too, I believe[74].” Rose-Marie Boylan stresses, “Well that is quite the article you have written, very impressive, sounds like structural, behavioral and economic violence of the worst kind”. Likewise, Mohammad Nawaz Bhatti comments, “It is really a great analysis of Indian mindset. I pray for the complete success of the people of our brother country, Nepal”[75].

Nepo-India has an age-old unique relationship of friendship and cooperation with a porous (open) border, deep-rooted culture and religion, people to people contact (kinship), similar food and same linguistic alphabets. Nepo-India Peace and Friendship Treaty of 1950 outlines the bedrock of the special relations between two nations. Even though, Nepal survives from Indian controlled economy. Nepalese bureaucracy highly polarizes because of RAW[76]‘s penetration in it. Nepal has never been colonized by external forces, but Nepali could not realize independence and sovereignty owing to India’s superior complexity, Prof. Pathak said. India’s complexity now turns to micro-level management in all dimensions. Moreover, none of the parties, institutions and professionals dare to speak or write against such India’s unjust strategies and atrocities fearing to lose either incumbent position, future opportunity or possible financial gain. However, in essence, all Nepali want to be free from all kinds of hegemonic encroachment.

Freedom to Construct Peace-Conflict Lifecycle

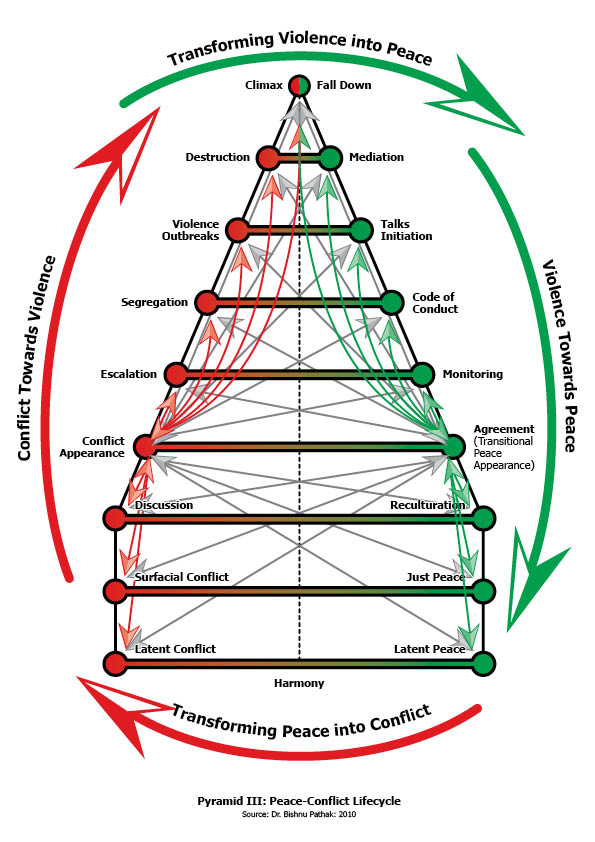

Peace-Conflict Lifecycle (PCL) is an innovative creation of Prof. Pathak[77]. The Lifecycle can be characterized into three dimensions: Pyramid I, Pyramid II, and Pyramid III.

The Pyramid I is a simple type of lifecycle which can easily be understood. In this case, the conflict may arise because of only one cause such as political or social and similar other. The Pyramid II is a compound type of lifecycle where two or more structural causes combine for the cause of conflict. The Pyramid III is a complex type of lifecycle where conflict may arise because of multiple webs and deep structural causes and their collateral factors. It means, conflict intensifies owing to structural political, ideological, cultural, social, economic and religious issues. The collateral causes shall be inequality in access to resources and opportunities, inadequate service delivery, injustice to the identities and beliefs, ineffective governance, inept transparency and accountability, intolerant leadership, inefficient bureaucracy and technocracy, and insipid diplomacy[78]. The previous Maoist launched People’s War in Nepal falls into this category of Pyramid III. The conflict similar to spiral in Pyramid III causes a huge loss of human lives, massive destroy of public and private properties.

Conflict occurs in the emotional human mind, and reaches a violent climax after passing through several stages or developments: discussion, appearance of conflict, escalation, segregation, outbreak of violence, and destruction (see Pyramid III). From the violent climax, the conflict steps down towards peace: first, one individual/group/institution in the conflict triumphs over the other; second, where there is a stalemate or balance between the conflicting parties; third, where there is extreme pressure from societies and international communities; and last, falls down by itself without applying any external/internal forces or pressures.

The steps of the process of de-escalation include direct and indirect mediation (including facilitation, if need be); formal or informal dialogue (initiation of talks) or negotiation; establishing a code of conduct for bargaining for ‘do’ or ‘does’ and ‘don’t ‘or ‘does not’; participant or non-participant monitoring mechanism for signed understandings, agreements and accords; and reculturation. Furthermore, the reculturation includes disarmament, demobilization, reinsertion, repatriation, resettlement, rehabilitation, reconciliation, and (re)integration (D2R6)[79].

In humane case, the conflict is solvable through negotiation or using the tools and techniques of conflict prevention, conflict settlement, conflict management, conflict resolution and conflict transformation in one or another way. In this study, the term transformation has not been used in latent conflict, surface conflict and open conflict, but at escalation, segregation, violent outbreak, destruction and climax stages. Transformation reciprocates in the peace developments, too. Nepal has not escaped from this transformation process. The conflict appearance, taper off, disappearance and reappearance of the lifecycle follow the thesis, antithesis and synthesis (TATS) system.

Before the initiation of violence, latent conflict appears at the bottom, further goes up as a surfacial conflict and then as an open conflict called discussion, but the number of conflicts and conflicting actors remain same, parallel to each other. There are many conflicts in the bottom of pyramid which gradually tapers off, intensifies and disappears, and peace is achieved until conflict reappears. Not all conflicts reach at the top of the pyramid, but many disappear on the way to going up in the changing political and socio-cultural dimensional context. Some disappear somewhere in the middle through mediation, negotiation or agreement, litigation, arbitration and adjudication. Only a few conflicts reach at the top crossing the several stages in the peace-conflict lifecycle pyramid.

Thus, conflict-peace development has its own lifecycle similar to ecosystem. The conflict-peace lifecycle has a complex set of relationships: habitat, living resources (production, distribution and consumption), interest and capability. If one part of lifecycle destroys or disappears, it leaves the significant impact everywhere. It does not leave impact on human beings alone, but all living organisms and species in the universe, ecosystem too.

Inverse, asymmetrical and crisscross relationships are found in between the cause and effect dimensions in the lifecycle pyramid. The lifecycle steps forward in structural, perpetual, manifest and latent dimensions. The cycle goes on or repeats uninterrupted from each minute to hour, hour to day, day to week, week to month and month to year. Such cycle belongs to intra- and inter-national, intra- and inter-regional, intra- and inter-social and intra[1]– and inter[2]-personal magnitudes. Usually, the peace-conflict lifecycle can be divided into three phases: before peace or violence, during peace or violence and after peace or violence. Moreover, the lifecycle follows attitude (love or hatred), behavior (peace or violence) and context (problem-solving or problem creating).

The strength of peace-to-conflict movement goes weak and further weaker towards the central axis of the pyramid. The vertical axis divides the roles of peace and conflicting character. The axis is simply called harmony. Compared to peace and harmony, conflict exits longer to attain change.

The fulfilling of people’s expectations, needs and demands shall only restore peace and harmony in every society despite the division of rich and poor, powerful and general populace, men and women, black and white and educated and illiterate.

Conflict and peace are the two sides of the same coin. Whatever changes take place on earth, it is because of both negative and positive conflicts. The negative (destructive) conflict is a quick deliverance of change, but positive (constructive) is a slow and lengthy process of change. From a general perspective, the negative conflict emerges in the (least) developing world due to lack of basic needs and freedoms unmet in the society – vertically and horizontally. The positive conflict usually takes place in developed nations.

For harmonious societal initiatives, Track II diplomacy is to be strengthened to create a pressure to both Track I and Track III. Therefore, there is a need for harmony in both Track (III and II) at home, work and community. These Tracks (people and professionals) voices are to be applied in nations, regions and on earth. The fusion of social democracy in the countryside and market economy in the urban centers[80] may soon be a role model for universal harmony; no less so in a socially, culturally, economically and politically sensitive and conflict-prone countries like Nepal.

Prof. Pathak adjudges harmony as a human mindset for human security, mutual respect-trust, cooperation, and open mindedness since it promotes social justice, fundamental human rights and freedom, co-existence, and fraternity. It is a envision of individual and societal mindset for truth, justice, love and dignity without a hierarchy. The harmony fuses both conflict and peace characters. Nepal’s armed conflict in the past, peace process and transitional justice mechanism could not be an exception of this entire process or lifecycle.

Concluding Freedom

Prof. Pathak’s parents ingrained his mission with a single Guru-mantra[81]: “not to be a great-man, but an honest-one”. His deceased mother used to say, “You are born not to take, but deliver the services.” His parents’ straightforward deliverance of services was to seek truth and to ensure retributive and restorative justice for human dignity. The truth and justice for dignity synergize him to keep going ahead with a singular commitment of just peace and harmony among people in the universe. So, he is tirelessly contributing to this field accordingly.

According to Prof. Pathak, an independent, impartial and accountable separate high level truth-seeking Commission needs to be established in any post-conflict country to disclose the real facts before the victims and their family and the general public. The Commission discovers and reveals actual facts identifying the perpetrators. If the victims and their families demand to initiate retributive and restorative justices in transitional period, the Commission may assist them to seek justice prosecuting perpetrators related to war crimes and crimes against humanity who were not included either into amnesty or reconciliation processes.

The Commission may assist in redressing justice for the victims and their families or relatives recommending some reparations. Prof. Pathak noted that every victim and his/her family has the right to obtain prompt, fair and adequate compensation[82] in the form of reparation. The reparation can be in the form of restitution, rehabilitation, satisfaction, restoration of dignity, reputation and guarantees of non-repetition. Prosecution against perpetrator and reparation to the victim may assist the victim and his/her family to live and let live with full human dignity.

Dignity is a quality of being praiseworthy of honor. Prof. Pathak’s concept of dignity expresses the innate idea of rights to valued, respected and ethical treatment for each and every citizen of the nation. The dignity is a non-derogatory, inalienable and inherent right. The prime duty of the state is to respect, protect and promote human dignity without distinction of caste, ethnicity, race, sex, age, religion, class, religion, geography, color and profession.

Prof. Pathak is a man seeking justice where there is injustice; he is a man advocating peace and harmony where there is (armed) conflict; he is a man campaigning against the weapons market where there is warmongers; he is a man voicing for equity where there is unequal distribution of resources and opportunities; he is a man looking for freedom as a freedom fighter where there is military-mindset and/or autocracy; and he is a man looking for structural, institutional and individual change where there is a ‘quest for power, politics, property and privileges’. Prof. Pathak firmly believes that injustice happened anywhere is a struggle to justice everywhere.

@TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 18 Jan 2016

Meena Pathak, Bimip Pathak and Bimish Pathak - TRANSCEND Media Service